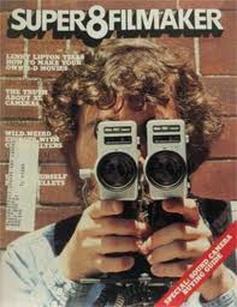

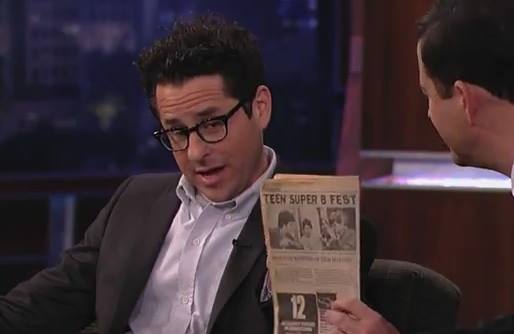

During an appearance on ABC's "Jimmy Kimmel Live" to promote the release of his film "Super 8" last July, J.J. Abrams was shown a yellowed newspaper article about "The Best Teen Super 8mm Films of '81" festival at L.A.'s Nuart Theater from March 1982. The screen cut to a tight shot of the photo above the title ("The Beardless Wonders of Film Making"), and there was 16-year-old Sanderson peering through the viewfinder of a Super 8 camera, alongside Abrams, Matt Reeves and festival organizer Gerard Ravel.

"A friend texted me and said, 'You're on Kimmel.' And I go, 'What are you talking about?' recalls Sanderson. His name wasn't mentioned, but Sanderson says he understands. "Matt and J.J. have worked together professionally," collaborating on the TV series "Felicity" and the film "Cloverfield," "so there's a story there," he says.

Gerard Ravel, J.J. Abrams, Matt Reeves and Mark Sanderson (left to right).

Gerard Ravel, J.J. Abrams, Matt Reeves and Mark Sanderson (left to right). Sanderson's name wasn't in the article, either, unless one counts the photo caption, but when it appeared in the paper's Calendar section shortly after the fest, his classmates at Santa Monica High School (aka Samohi) took notice.

"People were saying, 'Hey, man. You're in the paper,'" recalls Sanderson, who screened his 28-minute martial arts film "The Last Silent Swordsman" at the fest. "I said, 'What?' I look in the L.A. Times and, sure enough, 'Holy crap!' To be in the Calendar when you're 16 is like, wow!"

"These kids that were coming up to Mark were people we didn't even know," says Raj Makwana, who played an evil henchman in "Swordsman." "It was really weird."

The L.A. Times highlighted Abrams as the star of the fest, but in the article Ravel made clear he had big plans for all its participants. CAA had scouted this year's event and Disney Studios had expressed interest in promoting the next year's edition, he said. The filmmakers had signed "exclusive" management contracts with his Word of Mouth Productions, and he planned to strike a 35mm print of their shorts and tour the country with it, like he had done previously with surf films.

"I want to mold these film makers like a military organization because I'm a perfectionist," said Ravel in the Times article. "What I'm putting them through now is basic training."

It's unclear what the training consisted of beyond orders to refer all inquiries to him. Daniel Krishel and future "Super 8" cinematographer Larry Fong, who both had films in the fest, don't remember signing contracts with Ravel. But Sanderson was able to dig up a copy of his ("I save everything," he says), and it turns out that it was merely a 90-day non-exclusive license agreement for his film.

In the end, Ravel never got chance to lead his troops into battle. The next edition of the festival never happened, nor did the national tour with the 35mm print.

"I forgot where it ended," Sanderson says. "After the big hoopla, I don't know what roadblocks he ran into."

Perhaps Ravel came to the realization that while people around the country would shell out money to see the world's top surfers in action up on the big screen, they weren't exactly plotzing to see a grainy blow-up of no-budget amateur films. Besides, with the home video market taking off, touring the country with a celluloid print was quickly become an antiquated distribution model for niche films.Ravel subsequently turned his attention to his company NSI Video, which produced and distributed skateboarding and surf videos.

The failure of Ravel's grand plans didn't slow down the teen filmmakers. The Times article caught the attention of director Steven Spielberg, who had his reps hire Reeves and Abrams to clean his own teenage 8mm films and repair the splices for $300. What Spielberg handed over weren't prints struck from negatives, but the original reversal film that had passed through the camera. In other words, he was entrusting two 15-year-olds he had never met with the only existing copies of his films.

"It was insane," said Abrams on "Jimmy Kimmel Live." "It was like giving us the Mona Lisa and saying, 'Will you clean this?' And dogs are walking past it and siblings [as it's] on the floor of our bedroom. I wanted to steal a frame, because it said 'Written and directed by Steve Spielberg.' And I was like, 'Come on, we have to,' and Matt's like, 'No!' So we didn't."

While Sanderson and Reeves remain good friends to this day, the duo had dissolved their production company several years earlier to concentrate on individual projects.

"There was no particular reason [for the split]," says Sanderson, who formed a new production company (Titan Productions) with another friend, James Baumgarten, and printed up a batch of new stationary. "You start making movies together and I guess you sort of go, 'I'd like to take a stab at doing this myself.'"

Nonetheless, they still worked together in theater productions at school and helped out on each other's projects. Sanderson played a small part in Reeves' "Raging Bull"-esque boxing movie "The Loser," while Reeves co-starred as the chief of police in Sanderson's 45-minute spoof of the 1970s cop show "Ironside," which screened during lunch in the Humanities Center at Samohi in 1983.

Palisades resident the late Bert Convy in game show mode.

Palisades resident the late Bert Convy in game show mode. Over at Palisades High School, Abrams was building a reputation as a force to be reckoned with. In addition to making Super 8 films, he also found time to co-compose the score and sound effects for the low-budget 1982 sci-fi/horror film "Nightbeast" and star as Tevye in the school's production of "Fiddler on the Roof," which also featured "High Voltage" star Adam Rosefsky as student revolutionary Perchik, a part originated on Broadway by their friends' dad, actor/game show host Bert Convy.

Alice Krige's demonic latex stand-in from "Ghost Story" (1981).

Alice Krige's demonic latex stand-in from "Ghost Story" (1981). "Both J.J. and I were in contact with Dick Smith," Fong says. "That's why we had to mention ["Dick Smith's Do-It-Yourself Monster Make-Up Handbook"] in 'Super 8.' I think I wrote him and he said it's easier to just call, so we'd call [with questions] and he'd say, 'Get a piece of paper. I'm going to be talking fast.' He'd talk to anyone, any time of the day. J.J., of course, took it a step further by meeting him several times, including one time when Smith had a clearing out of his basement [in upstate New York]." Abrams, who was attending Sarah Lawrence College in Yonkers, NY, at the time, "bought a whole bunch of his props and he was nice enough to buy something for me and give it to me as a gift, which was the 'Ghost Story' (1981) naked torso of Alice Krige," Fong laughs. "I still have that actual prop. It's rotting, sadly, because latex foam rubber always does that."

Fong says Abrams also concocted a documentary film project to use as a vehicle to meet another makeup master, Rick Baker, who had recently won an Oscar for 1981's "An American Werewolf in London."

"J.J. called Baker and said, 'I'm doing a piece on you. Can I come visit you in your studio?'" Fong recalls. "I said, 'How do you think up this stuff? I can't believe you met Rick Baker. It's so unfair.'"

Act Three

After graduating from Samohi, Sanderson set out to make his first feature-length Super 8 film, "The Party Crashers of '65," a period comedy with 30 speaking parts, including ones for Reeves and another longtime classmate and collaborator Chad Savage (son of prolific TV writer Paul Savage), who died memorably in his 8th grade project "Dictator of Death," taking an imaginary bullet and falling off a wall with a packet of ketchup squeezed to his chest.

But as production dragged on, various members of the cast and crew moved away for college, including star Ian Murray, the grandson of comedian Jan Murray.

"We had to do reshoots and finish the film during spring and summer breaks," says Sanderson , who stayed at home and took classes through UCLA Extension and at Santa Monica College. "I'd go, 'I know you're going to hate me, but I've got to shoot these pick-ups of you acting to nobody because they're not here.'"

Four years prior to Sanderson's arrival at UCLA, Fong had tried to get into the film program there, but was rejected.

"I was thinking, 'How is this even going to happen? Maybe it's just a stupid dream,'" Fong recalls.

The son of a dentist, Fong had no family connections in the entertainment industry, and none of his neighbors in Rolling Hills, Calif., an hour south of L.A., were in the business, either. He decided to do responsible thing and finish up his undergraduate studies at UCLA by earning a degree in linguistics. But the filmmaking bug wouldn't go away, and a few years later he enrolled in the graduate film program at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, where his classmates included future top Hollywood directors Zack Snyder, Tarsem Singh and Michael Bay.

Throughout this time, Fong stayed in touch with Abrams.

"He'd always call up and say, 'Hey, let's have lunch,'" Fong says. "I never really knew why, to tell you the truth," he laughs. "We'd hang out for a little bit. We didn't really do anything. It just went on and on. I'd see him once or twice a year."

Back in Los Angeles on a break from his senior year at Sarah Lawrence in New York, Abrams ran into his old friend Jill Mazursky, the daughter of writer/director Paul Mazursky ("Down & Out in Beverly Hills," etc.), and the two decided to collaborate on a movie treatment, which Abrams' father then showed to Disney Studios head Jeffrey Katzenberg. Disney bought it, the tyro scribes penned the script, and in 1990 it was released as "Taking Care of Business," starring James Belushi and Charles Grodin. That same year, Abrams sold a script he wrote solo, "Regarding Henry."

"I went to New York when they were shooting and I went on the ["Regarding Henry"] set," Sanderson says. "It was the Pan-Am Building and I saw Harrison Ford. It was like this big expensive film, and he was paid $400,000 for the script."

Around this time, Sanderson teamed up with Greg Grunberg, a member of the Palisades crowd who had known Abrams since kindergarten, to write an action film script. While it generated interest from a high profile actor, it never sold. Nonetheless, "it was an exciting time," Sanderson says. "Everybody was coming up through the ranks doing their stuff."

Grunberg was subsequently given a small part in Reeves' directorial debut "The Pallbearer" (1996), starring David Schwimmer and Gwyneth Paltrow, and he went on to be a regular in the TV series "Felicity" (1998-2002), co-created by Abrams and Reeves, and "Alias" (2001-2006), created by Abrams, before being cast as one of the leads in "Heroes" (2006-2010).

Several of the Samohi filmmaking gang have also been involved in Abrams and Reeves' professional projects, including Lawrence Trilling, who served as a producer and sometime director on "Felicity" and "Alias" and now fills the same role on NBC's "Parenthood," and Savage, who was a co-producer on "Felicity," "Alias" and, more recently, "Friday Night Lights" (2007-2011).

After graduating from the Art Center College of Design, Fong quickly found work as a cinematographer shooting commercials and music videos, including R.E.M.'s award-winning clip for "Losing My Religion" (1991), directed by former classmate Tarsem Singh. But work in film and television was elusive.

"You go to film school because you want to do films, but I couldn't get arrested shooting an indie for free anywhere," Fong laments. "In a dozen years shooting, I did two tiny independent films. No one was interested in me. I was thinking, 'Who am I going to work with in film? I'm never going to work with Scorsese or Spielberg or any of those people?' Then my agent would say things like, 'It's going to happen with someone you know, like your old friends.' And I'd say, 'What are you talking about?' Then it turns out it's exactly true."

An image from the movie "300," shot by Larry Fong.

An image from the movie "300," shot by Larry Fong. "He said, 'I know you don't want to do TV, but I have a script. Is there any way you just might want to shoot it?'" Fong remembers. "I said, 'Oh, yes!'" he laughs.

Two years later, Snyder, who had worked with Fong on numerous commercials, hired him to shoot his second feature film directorial effort, "300" (2006), and the pair went on to collaborate on "Watchmen" (2009) and "Sucker Punch" (2011).

For the most part, Sanderson forged his own path. After graduating from UCLA in 1989, he spent the next six years working as waiter while trying to catch the elusive big break. He wrote scripts alone and with Andrew Roperto, with whom he co-founded the sketch comedy group The Amazing Onionheads, which self-produced a comedy pilot and recorded a novelty song ("Down with VEG") that got airplay on Dr. Demento's radio show.

Finally, in 1995, Sanderson waited his last table when he landed a gig as a staff writer on the MTV dating game show "Singled Out." In 1997, he co-wrote and co-produced the low-budget feature "Stingers," co-starring Seymour Cassel. The following year, his script for the WW2 coming of age drama "I'll Remember April" was put into production with director Bob Clark ("A Christmas Story") and co-stars Pat Morita and Haley Joel Osment, after languishing in development for several years.

If the passage of time weighed on Sanderson, the feeling was reinforced when the producers announced the project in the trades in 1996 and erroneously listed his age as 26.

"I said, 'I'm 30.' They said, 'Twenty-six sounds better.'" Sanderson says.

Krishel was in the film program for all four years at Beverly Hills High School, which would occasionally feature guest lectures by industry figures, such as director Sydney Pollack. But while he says making films "was a fun thing to do," he decided to pursue a career in law. Today, he's an attorney with his own practice in Woodland Hills, Calif., handling matters involving entertainment, real estate, labor, general business law.

Similarly, "High Voltage" star Adam Rosefsky took a few theater classes in college, but he says "it wasn't my calling." Today, he lives on the East Coast and works in biometrics sales, involving fingerprint and iris recognition technology.

It sounds like James Bond movie or "Mission Impossible."

"Yeah, except I can't watch those anymore," says Rosefsky, "because they look so fake to me now."

The real life advances in technology over the last three decades have not gone unnoticed by the Ravel's former charges. Sound is recorded eighteen frames before the image on Super 8mm film, so Sanderson would have to instruct his actors to wait a few beats after he called action before starting their lines. Film came in 50-foot cartridges that ran for 2.5 to 3 minutes (depending on whether one shot at 24 or 18 frames-per-second) and could cost close to $10 each.

"It was expensive for us, so we had to be almost damn sure that we rehearse a scene enough that it would be close to be the take," Sanderson observes. "Then we'd have to ship off the film to get processed, then we'd watch it and go, 'That one thing was a mistake, but it's good enough. Let's move on.'"

In the early '80s, decent Super 8 equipment could only be found in a handful of specialty camera shops or ordered over the phone from New York. Today, high def movie cameras are built into every smart phone, and video editing software is bundled with every new computer. Young filmmakers can do endless takes and review them instantly.

But high pixel counts, instant access and the ability to edit on a laptop at Starsbucks don't necessarily make for better films.

It could be that the proliferation of idiot-proof digital tools has diluted and obscured the pool of quality work. Or perhaps a generation conditioned to expect instant gratification doesn't have the stamina or the attention span to develop their craft. One thing is for sure: it has robbed today's young filmmakers of the romantic buzz Sanderson and his friends used to feel as a small band of artistes on the fringe of jock-dominated school culture, pining for the next issue of "Super 8 Filmmaker" magazine and the mysterious techniques it would reveal.

"Back in the day, I don't know how the hell I would've done it," says Makwana, who was Divine Weeks' guitarist. "These tools are helping us now get these and other creative projects out," as well as promote them via social media. "I wish we had them back then to make 'Swordsman.'"

Although Makwana was happy to help Sanderson with his films, his passion was music. But when Divine Weeks broke up in 1992 after releasing three independent albums, he left behind the gypsy life of a musician. Today, he has a wife, a six-year-old son and a straight job as the president and controller of a real estate services company, but he got a taste of his old life back in May when he and See played a few of the band's songs at a book release event at Book Soup in West Hollywood, and there are tentative plans for more promotional performances.

Of the others involved in "Swordsman, one is a lawyer and another is aerospace engineer. Festival organizer Ravel is now a real estate agent in Hermosa Beach, Calif. He did not respond to requests for an interview, but on his Facebook page he posted about providing the "Kimmel" producers with the newspaper article, hanging out in the show's green room and reconnecting with Abrams.

Not everyone appreciates the significance of his accomplishments.

"I went to Venice High to talk to my [teacher] friend's film class and they said, 'Have you made any big movies?'" Sanderson says. "I thought, 'Do you know how hard it is? Never mind. I thought I'd have a three-picture deal, too.'"

The pot at the end of the rainbow for screenwriters is not what it was back in the late '80s and early '90s, when people like Shane Black and Joe Eszterhas were making mult-million-dollar script sales right and left, but Sanderson is okay with it.

"I'm very happy to get paid to put words on paper," says Sanderson, who shares his philosophical musings about screenwriting in his blog My Blank Page. "I still have that wide-eyed kid inside of me that gets excited about being on a set and thinks, 'Oh, my gosh, this is for real.' I don't take it for granted."

For part one of The Real Kids of "Super 8," click here.

You can also read my Filmmaker Magazine interview with Super 8 film festival founder Gerard Ravel.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed