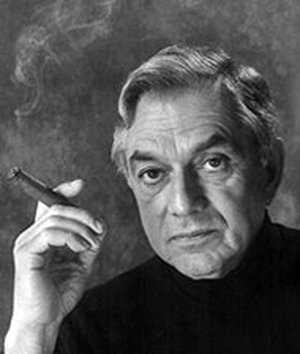

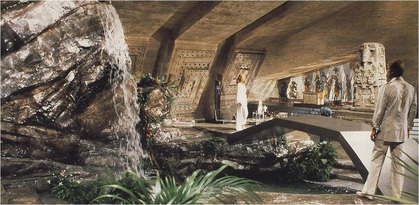

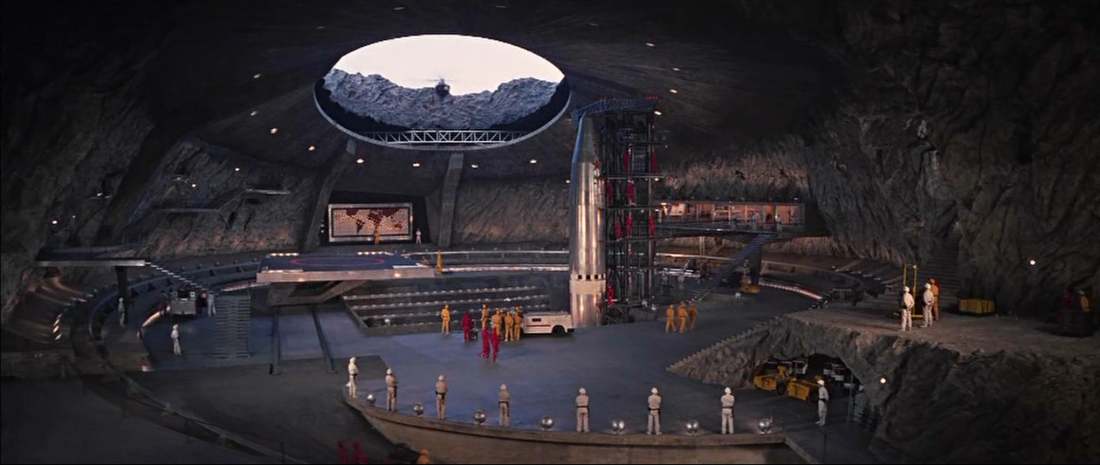

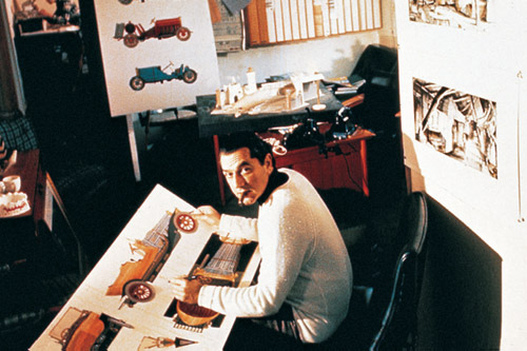

The 91-year-old former RAF fighter pilot set the visual template for the 007 franchise with his work on seven Bond films from 1962's "Dr. No" to 1979's "Moonraker," creating futuristic cars, weaponry and watercraft and numerous cavernous villain's lairs, exemplified by his massive volcano set for 1967's "You Only Live Twice," replete with operative monorail and heliport.

When I profiled Adam for The Hollywood Reporter on the occasion of his receiving the Art Directors Guild Lifetime Achievement Award in 2002, I wrote:

Equally at home in the Jet Age and the Age of Enlightenment, he has created the visual vernacular of the modern spy film with his jaw-dropping work on the James Bond films... articulated the darker side of our "neurotic technological age” in “Dr Strangelove,” and earned a pair of Oscars for his sumptuous recreations of 18th Century England in “Barry Lyndon” (1975) and “The Madness of King George” (1994)

Unfortunately, due to space limitations, I was only able to use a small handful of quotes from our lengthy conversation, which covered everything from his Bond work and his collaboration with director Stanley Kubrick to his opinions on the ominipresence of digital effects in modern cinema. So I've decided to present the interview below in, well, something close to its entirety.

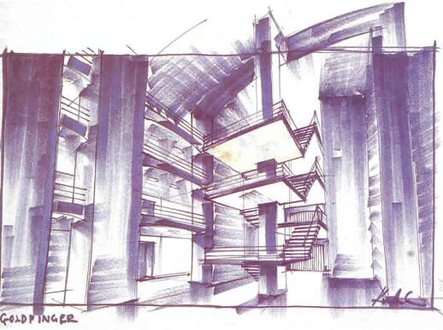

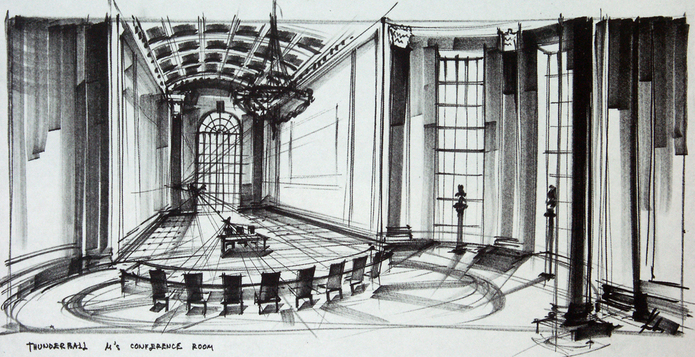

Adam: Yes. They’re not to be compared with other films, you see. Initially, of course, they did have the Fleming novels, but more and more the Fleming stories disappeared and the producers and the public seemed to rely more and more on the visual excitement of the film, meaning sets, locations, gadgets and everything else. It’s not like most films, where you get set a script by either a director or a director and producer, and you then visualize it, discuss it with the director in terms of concept, and once you more or less agree, then you start translating that script into visual terms. But the Bonds were somewhat different.

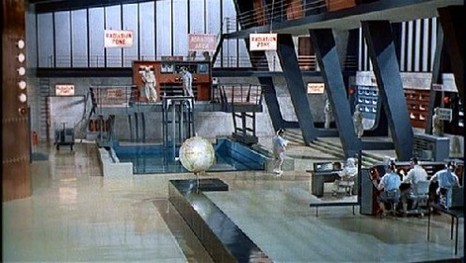

Longwell: That seemed to be particularly true with the volcano set on “You Only Live Twice” (1967).

Adam: We were desperate because we had covered about two thirds of Japan and we were looking for some of the locations that Fleming had mentioned, and of course they didn’t exist. We went in two helicopters and on one of the last days on the Southern island of Kyushu we found this area of volcanoes and that triggered a lot of ideas. It was decided that it would be interesting to have the villain inside the crater. So then I came up with this design concept, and I’ll never forget [Bond producer] Cubby Broccoli asking me how much it was going to cost. I had no idea, obviously. And he said, “Well, will a million dollars be enough?” And I said, “Sure.” [laughs] A million dollars in 1966 was a fortune! But then my worries started, you know. Once he had agreed, I said, “Well, can I do it for a million dollars?”

Also, they were in trouble. In those days already, those Bond films had a release date in about 3000-4000 cinemas, and we didn’t have a script! And this was the first glimmer we had of something visually exciting happening. So he felt, I suppose, a million dollars would be a reasonable expenditure if I come up with a really exciting concept.

Adam: Absolutely. I obviously tried to cover myself by calling in engineering firms and structural experts and all that, but it’s not like normal film set construction or design, and obviously everybody was experimenting. If someone does a skyscraper, it’s very easy to calculate, but I come up with a sliding lake of fiberglass 120 feet up on an inclination that was held by one cable, and nobody quite knew if it was going to work. And I realize that if something goes wrong, I’ll never work in film again. I had a lot of nervous moments.

Adam: Well, I think it’s probably both. I remember early in my career when I worked for [producer] Mike Todd on “Around the World in 80 Days,” he kept saying to me “think big,” and that somehow came natural to me. And also I think it’s possible something to do with my background as a boy growing up in Berlin with architects like [Ludwig] Mies van der Rohe, [Walter] Gropius and [Erich] Mendelsohn, who obviously had some influence on. I was fascinated by shapes and light and shade and big surfaces. The Bond films and obviously “Dr. Strangelove” gave me an opportunity to express myself.

Adam: I had all sorts of ambitions. I wanted to be an explorer… but I always used to be able to draw quite well, so from the age of 14 or 15 I was fascinated by films and also by the stage, and I hadn’t quite made up my mind in which direction I wanted to go. Then after the war it became apparent that I really wanted to design for films. Even before the war – in 1937-38, when I was 17 – I studied architecture not to become an architect, but to have a good grounding for film design.

Longwell: What inspired you to get into production design?

Adam: Well, I was attracted to films by chance. In those days – I’m talking in 1937 – the British film industry was run by three Hungarians called the Kordas (brothers Alexander, Vincent and Zoltan). I met Vincent Korda, who was the art director/production designer, when they were shooting a film with Marlene Dietrich called “Knights Without Armor,”and he was very nice to me and said, why not [become an art director]? But he said I felt I needed a certain architectural background, and that’s why I studied architecture.

Longwell: You were just a boy at that point. How did you happen to meet him?

Adam: Well, it’s a long story. My mother in those days had a boarding house in London, and one of the people staying there was a young Hungarian painter who became a camera assistant on a Korda production with [cinematographer] Jack Cardiff. And he took me to meet Vincent Korda, and that’s how it all started.

Longwell: Where did you study at?

Adam: I studied architecture at the Bartlett School at University College in London. I was also what they call "articled" with a firm of architects. It’s like an intern. You draw, but you also get practical experience. And then the war came, so that put a stop to all that.

Adam: Yes, I think that’s true, because I was always enormously attracted to speed, adventure and excitement, so certainly it somehow found a reflection in some of my Bond designs, without any doubt. And also in hindsight when you look back at those films – and you were mentioning the crater in “You Only Live Twice” and “Moonraker” – it’s one thing to put things on paper, but it needs quite a lot of courage to come up with concepts and constructions that basically have never been done before. So my past probably helped me at that.

Longwell: Working on the Bond films, it must’ve been enormously exciting to be given such a humongous toy chest to play with.

Adam: It was like therapy in a way, because when you work on other films you have to be disciplined by the script, which in a way is the backbone of everything, even though you can play with your imagination, but you are more limited. On the Bonds, the sky was limit, and that happened really after the success of “Dr. No.”

Adam: I had worked for Cubby Broccoli before on two or three films. The film that was very successful that I designed for him was a period film called “The Trials of Oscar Wilde,” which was something quite different. By this time, I think I had established a certain reputation as an art director/production designer. I had never worked with [“Dr. No” director] Terence Young, but he was really a fan of mine. He liked some of the previous films I done, so he gave me carte blanche. And I don’t think they expected me to come up with what I did, but it just happened to turn out that way.

Longwell: Why do you think your work on “Dr. No” turned out so well?

Adam: There was a lot of luck. When I designed “Dr. No,” everything sort of worked out right. The main unit was working in Jamaica and I was left to my own devices. The studio was here in England. I suddenly came up with the idea that it would be fun to, apart from the tongue-in-the-cheek element, to express our technological age, which I hadn’t seen at that time, except going back to films like Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” [1927]. For many, many years, we used the same way of building the sets and they were never really reflecting this neurotic technological age that we were living in. So this gave me an opportunity, and I again was very fortunate to have the right team of people with me. I was working at Pinewood; I had worked there before. I had wonderful construction people who all rose to the challenge, because I made it quite clear that I didn’t want to use old studio methods. I wanted new material, experiments with new ideas and so on. I’ve found, in my experience, that if I have a good team of people collaborating with me, I can use my imagination to any extent I can. I’ve been very lucky that.

Also, on ‘Dr. No,’ there was no one looking over my shoulder. So when the two producers, Harry [Saltzman] and Cubby, and [director] Terence Young came back from Jamaica, I had three or four stages at Pinewood filled with sets, and nobody had seen any designs for those sets. Terence was the first one to look at them, and he loved them. And, of course, once the director loves them, well, the producers also liked them. And everybody got excited, and it became like a democratic society. Everybody came up with ideas, and it really was in a way the basis for the future Bonds.

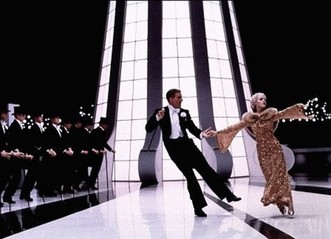

Adam: I call it the Tarantula Room. I’m delighted you say that, because I think it is one of my favorite sets, because it is so simple and theatrical or stylized. I think it somehow became the basis for some of the later Bond designs and certainly encouraged me to not only stylize Bond films but other films as well with rather simple means. Because this set was an afterthought and I had no money left. I think I had 450 pounds left. So I really had to come up with something very quickly that was very easy to construct and at the same time create a very important effect. It really worked. It’s amazing how people whose artistic judgment I respect always come back to this set.

Adam: No. I don’t think it ever restricted me. I’ve worked on, collaborated on or designed maybe 89 films. Today, I’m more interested in the story, the actors, directors and the people I work with, because you have to also enjoy what you’re doing. Although, I can’t complain. I had a good time on the Bonds, but they were an enormous, strain.

Longwell: Today, digital effects are often used excessively and badly. Reals set and miniatures are so much more rich and real.

Adam: Yes. everything you said, I agree with, and I’ve said it at lectures and talks and so on. I think it’s a very useful and wonderful tool, and it should be used as such, but it should not be used as a means to an end. If a whole film is done with digital effects, you know it’s artificial and you miss the reality of sets and locations. And I think it also must have a detrimental effect on serious acting, because for actors just to be in front of a green screen… Because I’m used to working with actors who possibly came from the theater who like to use props and like to feel the atmosphere of a set and feel at home in it. So I think it is great technical progress, but it has to be used as a tool, like anything else.

Adam: You’re absolutely right. On the other hand, “The Spy Who Loved Me” was one of the better ones. I mean, I liked the initial ones like “Dr. No” and “Goldfinger.” It upsets me if it’s been badly lit or badly shot, but if it’s well-filmed…

Longwell: You designed a lot of vehicles for these films, too. Was that something you enjoyed?

Adam: Yes. That’s the Boy Scout or the ex-fighter pilot in me – whichever way you like to look at it.

Longwell: Do you find your designs being imitated in real life?

Adam: People keep asking me that. I must say, I don’t look for it, but when I have exhibitions or books are published, other people say, “My God, you’ve been imitated” or “This has been copied.” I don’t know. At one stage, I thought I could design anything, no problem. When I did “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang” [1968] and I had to design a sexy looking car at the turn of the last century… It wasn’t so much that it had to fly or be a hovercraft, but just to make it look attractive was quite a challenge. Some people who worked for me then still say, “My God, you were a pain in the ass,” because we would build the mock-ups and I’d keep changing it until I finally thought it was right.

Longwell: You also made two films with Stanley Kubrick, “Dr. Strangelove” [1964] and “Barry Lyndon” [1975]. How did you get involved with him?

Adam: He had just arrived in England and he asked to see “Dr. No,” and after he saw it, he called me and asked me to meet with him, because he very much liked my work, and we immediately hit it off. It was an incredible start of a relationship, because we were both rather young and were sharing a lot of ideas together. I think in all my experience, I’ve never been quite that close to a director as I was with him, particularly on “Strangelove.”

Longwell: Was he someone who told you “go crazy,” or was he very hands-on and controlling?

Adam: No. It was a strange happening. We were sitting together at a table in his or my apartment, and we were going through what was then the script and I was sort of doodling on a pad in front of me, and he immediately liked the stuff I was doing. I had heard of his reputation and so on, and I thought, Well, everybody’s wrong. [laughs] He likes my stuff! I was in a way in seventh heaven.

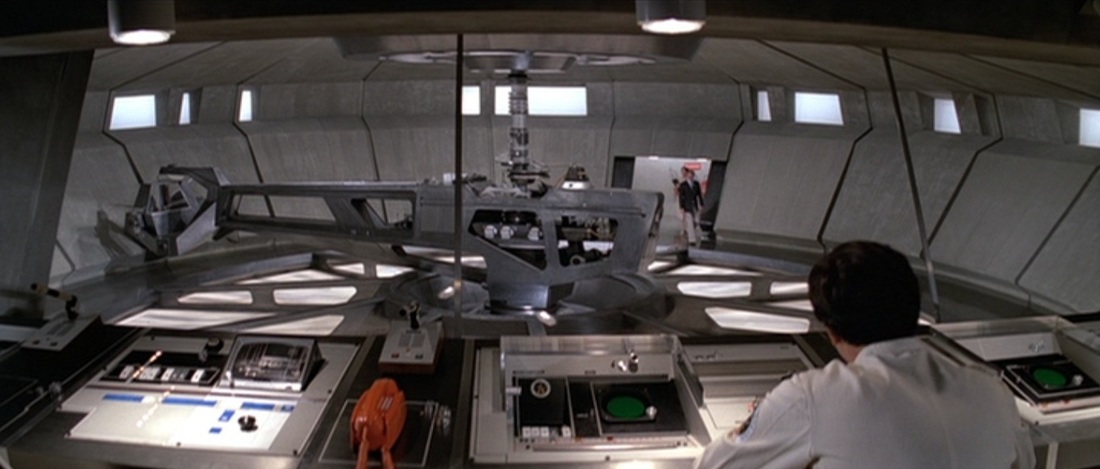

Longwell: When you designed the interior of the B-52 for “Dr. Strangelove,” how much of it was based on the real plane and how much of it was your imagination?

Adam: I think almost everything was available. Even though it was on the restricted list or something, there were all these technical magazines like Flight, and you could really construct a very accurate reproduction of that aircraft. The only thing we didn’t know was the CRM code. And I had a very good assistant who was working with me. We sometimes call them “nuts and bolt men,” who are wonderful with bits and pieces. We finally came up with the CRM design. Of course, now it’s history, but at some stage, we invited some American Air Force personnel to visit the set, and they went white because it was so accurate.

The next day, I got a memo from Stanley saying that I’d better make sure that all my references were because we might be investigated by the FBI or the CIA.

Adam: Completely.

Longwell: Did anyone ever let on that it might have any resemblance to the real War Room?

Adam: There’s an anecdote. How true it is I don’t know, but it’s been quoted that when Reagan became president he asked his chief of staff if he could see the War Room. He said, “What War Room?”Reagan said, “The War Room of the Pentagon shown in ‘Dr. Strangelove.’” It may be true, I don’t know.

Longwell: “Barry Lyndon” was entirely different – a British period piece that was shot without the use of electric lights.

Adam: His concept was to do all his night scenes by candlelight. That was an innovation, so we were experimenting with single wick, double wick, triple wick candles, and it became a nightmare. Some of them were non-drip, but they did drip, and the heat generated by hundreds of candles was sometimes enormous, particularly when we were filming in stately homes, so I had to come up with heat shields to protect their paintings and ceilings from all that candlepower.

Longwell: Did it ever annoy that so much effort was being exerted for Kubrick’s stylistic conceit?

Adam: Yes. But it was for a different reason. Before then, I always believed, fine, use locations as much as you like, but many things I felt I could better in a studio environment. But Stanley wouldn’t hear of it because he thought the most economical way to do that picture was on location. On that level, of course, he was proved completely wrong. It was an unhappy experience for me, but I think it would be too long to go into all that. And I think it was also an unhappy experience for Stanley, because remember by this time he had done “Clockwork Orange” and he had received a lot of threatening letters, so he was more reluctant to leave the so-called security of his home to go out and look at locations, so for weeks and weeks we didn’t. Certainly, he didn’t. So it wasn’t the happiest of films. But, you know, in hindsight, it was still a beautiful looking film.

Adam: Yes. I don’t whether he started with Ryan. I mean, we all ganged up on him when he decided, but, you know, once Stanley decided, that was it.

Longwell: I thought it might’ve just been an economic consideration, because he was a huge star at the time.

Adam: I think he actually wanted him. I have a sneaking suspicion, and I may be wrong but Stanley always wanted to do a film of Napoleon, and he would’ve done an absolutely brilliant job. He had more research than anyone else in the world on Napoleon, and I always felt he did “Barry Lyndon’ as a sort of rehearsal for Napoleon, because we staged a big island battle sequence between the British and the French with gigantically long tracking shots, a thousand meters long.

Adam: There are obviously a number of films. I still think in a way that “Dr. Strangelove” was one of the most important films that I’ve done, because if you really analyze my design for the War Room, it is really rather simple. It’s big and claustrophobic, but again I think that theatrical style paid off. The actors everybody else felt it and it seemed to be a very integral part of the dramatic action of the film. And I liked doing some of the Bond pictures, obviously, because they gave enormous liberty to my imagination. But I always like period pictures. I liked doing “Pennies from Heaven” at MGM in Hollywood in 1981. I liked "Addams Family Values" [1993] and pictures like that, because I could relate to Charles Addams and his New Yorker cartoons. But there’s a whole list of films. I’d really have to think about it. You have to give me more warning. [laughs]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed