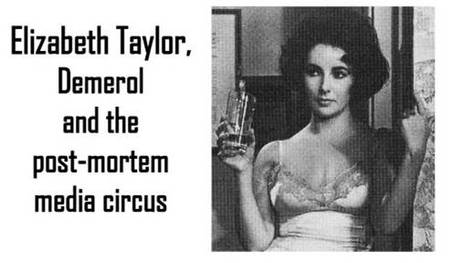

The bottle belonged to a man named B.J., who had appropriated it during his stint as one of Taylor's assistants in New York City in late '70s, a time when she was so heavy she was portrayed by John Belushi in drag on "SNL," munching on a chicken leg.

B.J. showed it to me in 1989, when we were working together at the Sunset Blvd. offices of Celebrity Service, which provided clients not with high-end escorts or limos, as some confused callers assumed, but contact information (agent, publicist, etc.) for film and TV stars and other notable public figures.

As we rifled through the files, B.J. would regale with stories of his days in New York, including tidbits about people like Taylor and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, as well as tales of weekends spent at gay sex clubs in the Meat Packing District, like the one about the time he stepped into a cab after long "shift" at the Mine Shaft and the driver looked in the rearview mirror and said, "Hey, buddy, what's that stuff on your cap?"

I was fresh out of UCLA Film School at the time, but I'd seen and heard enough not to be shocked by mere bathhouse debauchery. If anything robbed me of my innocence, it's what I came to call Celebrity Festivals of Death.

Whenever news organizations caught wind that a celebrity might be dead or at least packing their bags for The Hereafter, our phones would light up with calls for their rep, as well of those of others who had worked with them, loved them or, it seemed, once breathed the same air.

Eager to protect their "scoop," the intrepid journalists from Entertainment Tonight, Variety, National Enquirer, Reuters, et al, wouldn't actually tell us the star in question had passed, but after the fifteenth call in a row for Frank Sinatra or Richard Pryor, we'd catch on and ask, "So . . . did he die?" to which they'd typically reply, "We're not sure." Thus the responsibility of confirming the death often fell in our laps.

With the TMZ-ing of celebrity reporting in recent years, this might all seem a little quaint now, but it affected me enough that I was moved to write an article about it, titled Celebrity Death Feeding Frenzy. If it had been written within the last ten years, it definitely would've mentioned Taylor, who's probably been the subject of several false death rumors during the last two months alone, as she lingered in the hospital. And as sad as her predicament was, you can bet the journalists chasing the story were buzzing on adrenalin, just as they would be covering a plane crash, a war or a similar large-scale tragedy.

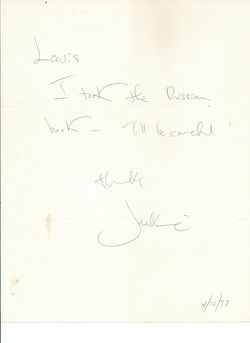

As for B.J., he died of AIDS in December of 1989. Given his raucous bathhouse tales and his occasional observation that he was in "the waiting to die period of [his] life," we should've suspected something was up. But he never looked or acted sick until that November, when he went to the hospital with a bad cough and never emerged alive. I inherited his job as the editor of the company's daily newsletter, the Celebrity Bulletin, along with a note from Jackie O that he'd gotten from friend who worked with her at Doubleday Publishing ("Lewis ... I took the Russia book. I'll be careful. Thanks, Jackie.") I scoured his desk for the bottle of Demerol, but it was nowhere to be found.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed