After 15 minutes of fights, car chases and flying ninja throwing stars, Ravel had seen enough.

"He said, 'That's great! I want to put it in our festival,'" recalls Sanderson, who directed the film.

Just like that, Sanderson was in. There was only one small catch: He had to sign an exclusive management contract with Ravel's Word of Mouth Productions.

"My dad had to co-sign it because I was underage," Sanderson recalls. "[Ravel] said, 'Now, you're going to be approached by agents...' I was thinking, 'Who wants a 16-year-old kid to make a movie?'"

The more pertinent question was, "Is anyone interested in seeing a bunch of no-budget movies made by teenagers?"

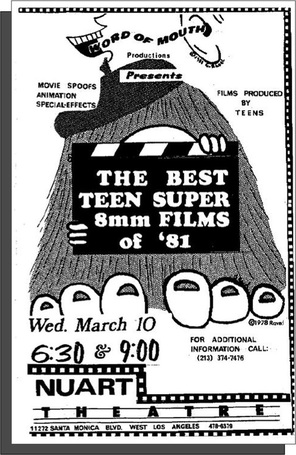

Mark got the answer as his car approached the Nuart on the night of the event and he saw the line of people waiting to get in the theater circling around the block. And it wasn't just the casts and crews and their friends and family. There was a TV crew and professional still photographers snapping pictures. Inside the auditorium, the audience applauded, cheered and gasped at the appropriate moments. The six-thirty show was a sell-out, and the nine o'clock show was nearly three-quarters full.

"It was crazy exciting," Sanderson says. "Gerard sold the hell out of it. He was like P.T. Barnum." Although, "I don't remember any agents walking around saying, 'Here's my card,'" he laughs.

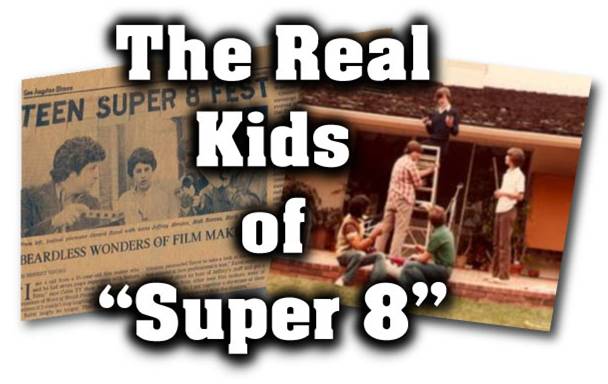

It might not be on par with the future progenitors of the French New Wave coming together to publish Cahiers du Cinema in the 1950s, but in an age when the movie landscape is dominated 3D renderings of computer-generated comic book characters, the event stands as a significant seminal moment in contemporary film history.

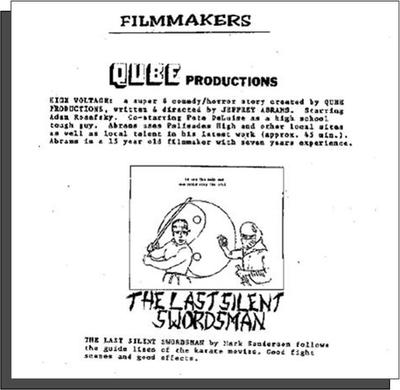

One of the films screened that night was the 45-minute horror-comedy "High Voltage," made by 15-year-old Jeffrey (J.J.) Abrams, today famous as the creator of the TV series "Felicity," "Alias" and "Lost" and the director of "Mission: Impossible III," the big-screen "Star Trek" reboot and the recent Steven Spielberg-produced hit "Super 8," which, in a bit of autographical data mining, revolves around a group of 13-year-old amateur filmmakers in 1979. Another was the 28-minute Hitchockian thriller "Stiletto" by Matt Reeves, who went on to co-create the series "Felicity" with Abrams and direct the films "Cloverfield" (produced by Abrams) and "Let Me In." The program also included the 15-minute spoof "Toast Encounters of the Burnt Kind" directed by Larry Fong, the cinematographer for "Lost" and "Super 8," which, in an interesting bit of gestalt, has been cited for its visual debt to Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" (1979).

Others in this community of teen filmmakers went on to be prominent players in such TV shows such as "Heroes," "Parenthood" and "21 Jump Street."

Fong says he doesn't remember much about the event itself, but its key players never left his orbit.

"From time to time, J.J. would have a party and half those people would be there, and I still see them," says Fong, whose credits also include multiple collaborations with director Zack Snyder ("300," "Watchmen" and "Sucker Punch") and a trio MTV VMA Video of the Year Award-winners for R.E.M., Van Halen and the Goo Goo Dolls. "When you're a friend of J.J., it's kind of this weird club where you end up seeing each other over the decades even when none of us are doing anything. He hires you or you're part of his company and you stay there. It's kind of a family thing."

By the time of the festival, Sanderson's eyes had been on the prize for nearly half a decade. He and classmate Reeves began making films together in 1977, the year of "Star Wars," crafting their own versions of the secret agent and kung fu movies that fascinated them as preteen boys.

"We had tremendous output, at least a movie or two a year," Sanderson recalls. "The films would be 20 minutes, then later they got to 45. We lived a block from each other, so it made it quite easy to work on stuff. His house was sort of the movie studio with all the equipment."

The duo formed their own production company, R&S Studios (for Reeves & Sanderson). Reeves assumed the title of president; Sanderson was vice president and head of security. They enlisted their friends as actors, printed stationary and published a newsletter to publicize their efforts.

"It was vertical integration," Sanderson says. "We not only would shoot the films and edit them, we'd put up posters around the neighborhood then show them for money to whoever would come. We believed in it that much, like, 'Oh, we're moguls.'"

Ravel too had visions of moguldom. An avid surfer since 1962, he had been touring the country showing surfing films. This was in the days before the home video revolution, when niche films had few avenues of distribution and the random access instant gratification of YouTube, et al, was still decades away. He would rent a theater or hall in each city, pass out flyers and put up posters around town, and enthusiasts would turn out in droves to see the wet-suited heroes they'd seen frozen in the pages of Surfer Magazine come to life and shoot the curl in super-slow motion.

By the turn of the '80s, the iconoclastic "movie brats" of the late '60s of early '70s had solidified their status as mainstream moneymaking machines. It wasn't just Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, who scored a blockbuster with their nostalgic thrill ride "Raiders of the Lost Ark" in the summer of 1981. Darker-minded compatriots like Brian De Palma ("Carrie," "Dressed to Kill"), John Carpenter ("Halloween," "Escape from New York") and Paul Schrader ("American Gigolo") were also turning out hits. Betting on the next generation of young filmmaking talent didn't seem like a bad idea.

Ravel launched "Word of Mouth" as a showcase for local amateur filmmakers, taking advantage of government regulations at the time requiring cable systems in communities with 3,500 or more subscribers to set aside TV channels for locals to show their self-produced programming and provide the equipment and the studio time for them to make it.

Reeves was flipping through the channels one day in June of 1981 when he stumbled upon an installment of "Word of Mouth" featuring a collection of Super 8 horror movies followed by an interview with the 14-year-old filmmaker, who had been making movies since the age of 7 when he borrowed his parents camera to make a stop-motion clay animation short.

At the end of the program, there was ad cheekily proclaiming, “Air your shorts." Eager to get on the action, Reeves called the number on screen and soon he too was showing and discussing his films on the show. Ravel told Reeves he should meet the kid whose films caught his eye, Jeffrey Abrams. An introduction was made, and the two became friends. When Gerard asked if they knew of another kid who might have a film for the fest, Reeves referred him to Sanderson.

Fong met Abrams around the same time, when he made the 42-mile trek from his home in Rolling Hills, Calif., with a friend to spend the weekend with the latter's divorced dad, who lived across from the Abrams family in the Pacific Palisades, a few miles north of Santa Monica.

"We were about four years older, but [J.J.] would come over and bug us and vice versa," Fong says. "He invited me to his house and he was just this whirlwind of energy and multiple talents even at that young age. His room was full of musical instruments and magic and monster books and models and stuff like that, and I was interested in all the same things, so we connected and became friends, even though at that age it's funny to be friends with someone that much younger."

Like Abrams, Fong was captivated by the works of Spielberg and horrormeisters Carpenter and David Cronenberg. He had been making Super 8 movies since junior high, both live action and stop-motion and cell animation, and experimenting with makeup effects, and Abrams called on him to help craft the transformation scenes for "High Voltage."

"There's this part where [a character] has these reactions to being electrocuted, and his arm swells up and ripples a la 'Altered States,'" Fong recalls. "I used bladders and stockings and latex and tubes."

Fong's own film "Toast Encounters" was a veritable special effects spectacular, featuring levitating sandwiches manipulated with an off-camera fishing pole, stop-motion-animated dancing foam rubber toast creatures and a spectacular scene in which the protagonist witnesses a toaster spacecraft land on a schoolyard, built in miniature.

Like their fictional counterparts in "Super 8," the real life teen auteurs weren't above incorporating snatches of real life drama into their films for added "production value." Daniel Krishel remembers being in the middle of shooting a robbery scene for his film "Six Inches of Death" in an alley behind his house, using fake guns and a knife, when the Beverly Hills Police rolled up, sirens flashing. He showed them his camera and assured them that they were merely students shooting a movie. As the cops returned to their squad car, Krishel told one of his actors to lay on the ground and play dead, then placed the camera on the ground in front of him and rolled film.

"The last shot of the film you see is the cops surrounding him with their car and their lights and everything," Krishel says. "For a student film, to have the actual Beverly Hills Police in my movie, it looked pretty neat, pretty real. And I remember that caught a lot people [at the festival] by surprise."

The juvenile movie crew in "Super 8" lives in a quaint, isolated Ohio town. Their big dream is getting their film into the Cleveland International Super 8 Film Festival. To their parents, factory workers and cops, making short films is viewed as a frivolous hobby, at best.

Not so for the real life Super 8 auteurs in Abrams circle.

"My parents bought me my first camera," Sanderson points out. "They were artists in their day, but never got to do it. My dad," an aerospace engineer, "was a budding singer. He used to send tapes to Capitol Records and sing in the piano bars, and my mom wanted to be a Rockettes dancer. They were always saying, 'Go after your dreams.'"

Growing up in Santa Monica in the '70s, "it was the back lot, basically," says Sanderson. " 'Charlie's Angels,' 'Starsky & Hutch,' 'Quincy,' all these shows that we watched and followed, would be shooting there every week, and after school we'd go off and hang around the set. The gaffers would take us under their wing and say, 'Hey, sit here.'" Becoming a filmmaker "didn't seem like a crazy dream we were trying to chase," he says, "because it was happening around us.'"

Abrams' father Gerald W. Abrams was a successful TV movie producer ("An Act of Love," "Berlin Tunnel 21"). Writer/director Nicholas Meyer ("Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan") attended J.J.'s bar mitzvah and special effects pioneer Douglas Trumbull(“2001: A Space Odyssey") sent him note of encouragement when he was 11.

For the leads in "High Voltage," Abrams called on friends Adam Rosefsky, whose father was local TV financial guru Robert S. Rosefsky, and Peter DeLuise, the son of comic actor Dom DeLuise ("History of the World, Part I," "The Cannonball Run") and, later, one of the stars of Fox's "21 Jump Street" (1987-1991) alongside Johnny Depp.

"The Palisades was one of the areas where the Hollywood folks lived," says Rosefsky. "So, like anywhere else, you sort of follow in the footsteps of your father."

Sanderson and Reeves attended Santa Monica High School (aka Samohi), where the baseball team's roster included Charlie Sheen (whose father Martin sheen was riding high as the star of "Apocalypse Now"), future "Lois & Clark" star Dean Cain (stepson of director Christopher Cain) and Brat Pack heartthrob-to-be Rob Lowe. In theater class, the pair acted alongside future Oscar-winner Robert Downey Jr., who had already appeared in several films directed by his father, noted underground filmmaker Robert Downey, best known for the cult classic "Putney Swope" (1969).

"He disappeared in 11th grade," Sanderson recalls. "Then one day we're watching 'Weird Science' and I'm like, 'Holy, shit! It's Robert Downey Jr.!'"

Also roaming the halls of Samohi was the youngest son of TV director Leo Penn and actress Eileen Ryan, Chris Penn, who would go on to co-star in such films as "The Wild Life" and "Reservoir Dogs" before succumbing to heart disease in 2006 at the age of 40. His older brother Sean had co-starred opposite Timothy Hutton in the movie "Taps" the previous fall and would shoot to fame that summer as Jeff Spicoli in 1982's "Fast Times and Ridgemont High."

The brass ring was clearly within reach. Big things were happening, and not just to remote, mythical figures in newspapers and magazines. Then, suddenly, Sanderson was one of those people, and his classmates weren't so jaded that they failed to take notice.

Check out The Real Kids of "Super 8," Part 2, in which I take a look at what happened in the wake of the fest, the teenage chutzpah of J.J. Abrams and where some of the lesser-known 40-something "kids" are today.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed