S T U N T S

Pasted in a corner of Eddie Smith's scrapbook is a small, yellowed newspaper clipping from 1969 telling of a helicopter crash on the set of a war movie in which a pilot and two stuntmen "escaped injury." The movie was "MASH"; Smith was one of the stuntmen; and as he walks across the den of his Culver City home on this spring day more than 30 years later, he still has a limp from that accident. Although he's free to grouse about the pain now, back then he held his tongue.

"I couldn't mess it up for the rest of the group, man," says Smith, 78. "We fought too hard. We had to show ourselves."

"I couldn't mess it up for the rest of the group, man," says Smith, 78. "We fought too hard. We had to show ourselves."

|

Do Tight TV Schedules Put Stunt Performers in Danger?

It was supposed to be part of a routine fight scene. But when 33-year-old stuntman John Bernecker fell from a balcony on the Georgia set of AMC’s “The Walking Dead” on July 12, something went wrong. He missed the safety padding by inches, and his head hit the concrete 22 feet below. He died five hours later in an Atlanta hospital after being taken off life support.

The incident has renewed long-simmering concerns about set safety, especially as they pertain to television. Thanks to the increasing proliferation of original scripted programming on cable and streaming outlets, more and more shows are one-upping each other with movie-quality stunts. But they’re still shot on tight, small-screen schedules (typically nine days for a 60-minute episode), on budgets dwarfed by their big-screen counterparts. “As safe as you try to make things, and as much as you try to control everything in your power, there’s always going to be a level of risk,” says stunt coordinator Norm Douglass, Emmy-nominated for Fox’s “Gotham.” 'Yes. And I do all my own lying.'

During his tenure as superspy James Bond, actor Roger Moore was often asked if he did his own stunts. His standard reply was, "Yes. And I do all my own lying." Today, stars far less witty and candid often boast that they're involved in virtually every piece of hair-raising action you see on the screen. In truth, they are most likely either a) starring in a stage-bound melodrama, or b) like Moore, doing their own lying.

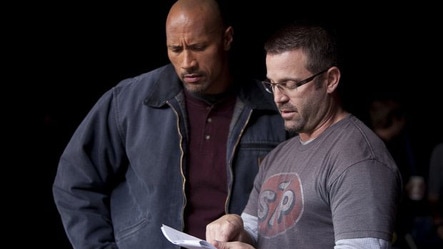

Writer/director Ric Roman Waugh with Dwayne Johnson on the set of "Snitch." Writer/director Ric Roman Waugh with Dwayne Johnson on the set of "Snitch."

There are faint scars on the face of Ric Roman Waugh that testify to the injuries he suffered during his years as a stuntman on films such as “Days of Thunder,” “True Romance,” “Hook” and “Lethal Weapon 2.”

But Waugh, son of the late Fred Waugh, a founding member of Stunts Unlimited, is more concerned with prison these days — specifically the unforgiving criminal justice system he depicts in his film “Snitch." “You’re not a criminal; you follow the rules of society, and then you make that one mistake … ,” Waugh says.  Stunt coordinator Conrad Palmisano.

The Good Fight

Stunt performers are gaining ground and respect at SAG. If you're an aspiring movie daredevil looking to join the Stunt Persons Union, don't waste your time: It doesn't exist. While there are fraternal organizations, such as Brand X, the Stuntmen's Association, Stunts Unlimited, the Stuntwomen's Association and the United Stuntwomen's Association, that provide members with status and a sense of community, it is the Screen Actors Guild that negotiates their contracts with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. Don't feel embarrassed if you weren't aware of this fact. Two decades ago, when stunt coordinator Conrad Palmisano ("Rush Hour 2," "Lethal Weapon 4") showed up at a SAG meeting to discuss stunt-community concerns, he found similar ignorance in the leadership of his own guild. "They told us to go to our own union," recalls Palmisano, who currently serves as president of the Stuntmen's Association. "From that time to this time, there's been tremendous improvement (in our relationship with SAG), but it's a project that's never really finished. You just have to keep working on it, inching forward." Where Credit Is Due

Should there be a special Oscar created for stunt people?

With the World Stunt Awards, the stunt community finally has the opportunity to honor its own, but many think it's high time that Hollywood's most august body, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, recognize them as well.

"Eighteen years ago, I started trying to get the Academy to establish a best stunt coordinating category, and they have just been totally against it," says Jack Gill, a stunt coordinator and second unit director whose credits include the recent "Showtime" and the upcoming "Austin Powers in Goldmember." "It just surprises me that we can't get them to move a little faster." |

Stunts Went Old School in Oscar-Nominated Films

Filmmakers used every digital tool available to amp up the action in “Deadpool.” In the film’s hyper-violent freeway chase scene, stunt performers were shot against green screens in vehicle interiors or otherwise bare soundstages, then virtually placed into (or hanging off of) careening CG autos alongside wholly-digital characters and a backdrop created with multi-camera plates of freeways in Detroit, Chicago, and Vancouver.

But sometimes the most innovative and effective approach is to dial back the digital technology and go old school as stunt coordinator and second unit director Mic Rodgers did on “Hacksaw Ridge,” the true story of a pacifist’s battlefield experiences in World War II. “For me, old is new,” says Rodgers. “We kept it as real and as in-the-camera as we could.” More Superhero Shows Raise the Bar for Television Stuntwork

With a quartet of Marvel series on Netflix and one on ABC (“Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.”), and nine series built around characters from the DC Comics universe airing across the broadcast networks, an unprecedented number of comic-book heroes are battling it out on the small screen in increasingly elaborate, Emmy-worthy action sequences.

While most of the shows’ protagonists are gifted with superhuman powers, the stunt teams still have to keep the action grounded in reality.

When stunt coordinator Anton Moon staged the slave ship mutiny for History Channel’s new miniseries adaptation of “Roots,” he had to deliver more than just exciting action with 20 stunt people and 200 extras. He had to make sure the fighting style accurately reflected the background of 18th century Mandinka captives, not modern action movie conventions.

“No kicking, punching, no head-butting — none of the old go-to favorites,” says Moon. “The Mandinka had to be very light-footed, very fast-moving, in contrast to the European sailors, who would throw a normal punch and move kind of heavy-footed.” Moon’s work in “Roots” is representative of the intricate, large-scale complex stunt work being done in television today on shows such as FX’s “American Horror Story: Hotel,” Netflix’s “Daredevil” and Syfy’s “The Expanse" ... 'Daredevil,' 'Black Sails' Take Movie-Style Stunts to TV

TV shows increasingly serve up big screen-style action, but that doesn't mean they have cushy movie schedules to pull it off. In my article in Variety, I explore the challenges faced by the stunt coordinators behind some of this year's most Emmy-worthy action sequences in Netflix's "Daredevil," Starz's "Black Sails" and NBC's "Chicago Fire."

They get thrown down stairs, tossed off buildings, set on fire, and no one knows their names. They risk life and limb to provide a film with jaw-dropping, heart-stopping action and then sit quietly by while the $20-million superstars accept kudos for their 60-foot free falls. They're stuntpeople, and they make it look easy, but it's anything but.

Giving Back

The Taurus World Stunt Awards Foundation supports those injured on the job. The World Stunt Awards do not exist just to give the stunt community an opportunity to pat itself on the back in front of a national TV audience, they also serve as a vehicle to raise funds for the Taurus World Stunt Awards Foundation, an organization that was established to help support stunt performers who have suffered debilitating injuries in the line of duty. "You have to be fairly catastrophically injured to qualify," says veteran stuntwoman Jeannie Epper-Kimack, who recently performed in such films as "Wild Wild West" and "The Princess Diaries" and sits on the six-person committee of veteran stunt performers that selects the grant recipients. "It has to be the result of a stunt-related event that occurred during the last year or during the making of a movie that was released last year. You can't be someone who was driving home from work and got in a car accident." |